As I suspect thousands of people did in the week after Gary’s death, my friends and I played OD&D to memorialize the man who invented our hobby.

My friend Jim was 19 in 1975. He played with Dave Arneson a couple of times when Arneson was out here at Conventions. He was in Lee Gold’s group (which he describes as being many large groups all amalgamated together) when Lee started Alarums & Excursions. Playing with Jim is, no shit, playing with part of gaming history.

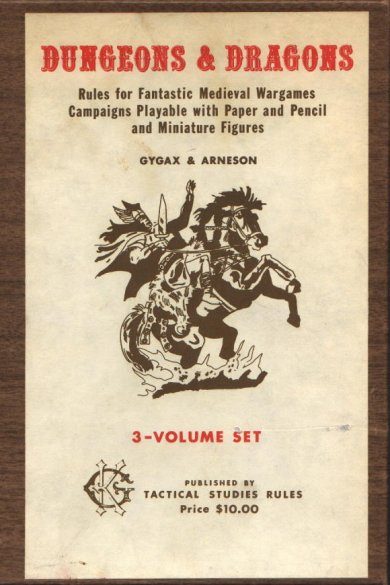

So Jim shows up last night after I suggested we play OD&D in memory of Gary with his original D&D “books.” By books here, I mean pamphlets. This was before AD&D, this was before the boxed sets we all grew up with. This was the original.

Jim was running the game section (because no one else wanted to) of a military shop in SoCal when D&D came out in 1974. Jim was already a wargamer at that point, playing games like Panzer Blitz. He loved fantasy and when D&D arrived he quickly became part of the phenomenon. He was in his late teens, just out of high school.

These pamphlets were expensive. They were the most expensive games you could buy. $10. You could take your girlfriend to dinner and a movie for $10. Well, a movie and Taco Bell maybe.

This was the first roleplaying game. Before this, there were wargames and strategy boardgames, but no RPGs. The idea did not exist. Furthermore, the notion of fantasy gaming as opposed to historical gaming was brand new as well.

Roleplaying Roleplaying

Jim shows up and says; “Ok! It’s November, 1975. Blackmoor just came out,” he says, showing us the 32 year old book, “but I haven’t read it yet so we can’t use the rules in there. But we CAN use the Greyhawk supplement! That means you can be a Thief now! Or a Paladin!”

Of course the real Jim has read Blackmoor a dozen times, but this is Jim from 1975. Jim is literally roleplaying the act of roleplaying in 1975, and we play along. Some amusement comes from the fact that the rest of us hadn’t even started grade school yet, but quickly we’re talking about what video games, if any, existed. Pong, certainly. But not Space Invaders. Caress of Steel had come out, Dark Side of the Moon was already 2 years old. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is already a year old. All the classic Yes albums were already a few years old, ditto Jethro Tull. Minstrel In The Gallery was just released and had I the presence of mind, I’d have put that on the iPod stereo. That’s a good album to roll dice by. Star Wars was not out yet, obviously, but Jaws was out! First blockbuster movie.

We open up the books, yellowing with age and begin reading. We recognize many of these terms and concepts but a lot of it is new to us. The art is really astonishing. Bad, oh yes, but also very charming. We begin making characters. DaveM, the wizard, DaveJ the Cleric, Craig the Fighter and I, the Thief. Really, I should have played the Paladin. My first D&D character was a Paladin. Ah well.

My thief needs a name! Of course we know that many of the things in D&D are named after the people who created it. The Wizard “Drawmij” is Jim Ward’s character. Vecna is an anagram of Vance, i.e. Jack Vance who Gygax borrowed his magic system from. Gary was the WORST offender in this regard. As S. John Ross said:

When I’m far from Gryrax, wandering around Castle Zagyg, fighting Xag-Ya and Xeg-Yi with the powers of my Ring of Gaxx and my Talisman of Zagy, I wonder “Who made all this stuff? He shouldn’t be so shy about putting his mark on it in some way.”

Even though I know this I’m still astonished to find, in the credits, the name Tom Keogh. “Oh my god.” Everyone wants to know what I’m reacting to, and I show them. “Reverse the names and you get Keogh Tom. Keoghtom. From which the magic item Keoghtom’s Ointment comes from.” A magic item that’s been in every edition of the book for 30 years. This may seem stupid to you but to us sitting around this table it’s like digging up dinosaur fossils. We’re archaeologists, exploring the past and discovering where we come from.

I asked Jim; “Jim, you know me. If I’d been playing this game back when it first came out, what kind of name would I have made up? Would I have made a silly name? A serious one? Stolen a name from somewhere?” Jim makes it a point never to answer a straight question when a story will do and so he told me that most of his names were stolen from books. I suddenly remembered how I named all my characters in my friend Brad’s campaign, and I immediately wrote “Duncan” on my character sheet.

In Brad’s campaign, all my PCs incorporated Dune characters into their names. Antony De Vries, Annon Corrino. So Duncan the thief is from Duncan Idaho. My friend Dave similarly named all his characters after the Bloodguard in The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant. Cail, Korik, etc… Understand that we weren’t playing characters anything like the characters whose names we stole, it was just a way of personalizing your character. Like putting a Rush sticker on your binder. It also became a tradition, something you did. Many of us saw nothing wrong with this, we didn’t think it harmed verisimilitude. Very quickly, the names, regardless of reference, stopped reminding us of anything other than “this character.”

The Thief

So, of course, Duncan the Thief. One thing I notice immediately. Thieves can do things. The other characters can’t. I don’t mean “there are things I can do no one else can” I mean the thief has a variety of options while the other characters each only have one. The fighter can only attack, the mage and cleric can only cast a spell, one spell. Whereas I can attack and gain bonuses from striking at someone if they don’t know I’m there. I can open locks, I can find traps, hide in shadows, move silently. Some kind of breakthrough happened between the original three books of D&D, and the Greyhawk supplement. Characters had special abilities. Anyone could attack, only the thief could do these things.

In point of fact, this would be the counter-revolution within D&D. The Thief marks the beginning of these battles, the ur-edition war. The first of it’s kind. Because there’s no reason the thief should have a “Move Silently” ability. Why can’t a wizard try and move silently?

The thief was the first character created for the dungeon. He’s not a thief, he’s a professional dungeoneer. The other characters, the Cleric, the Magic-user, the Fighting-man, had roles outside the dungeon, had roles on the battlefield. That’s where they first came from.

But the thief was adapted for the dungeon. In a sense, there should be no thief, because everyone should be able to do what he’s trying to do. If the game’s about Dungeons then all the characters should be trying to move silently, hide in shadows, etc….

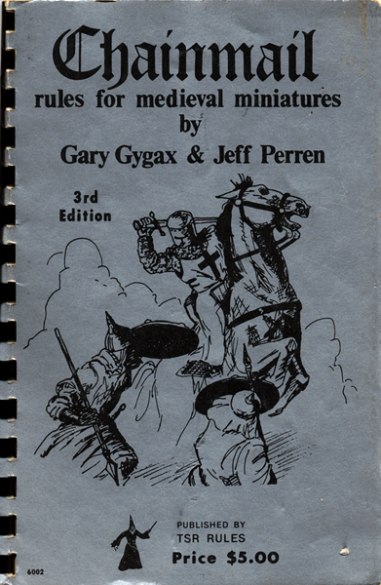

Chainmail

As we’re making our mans, Jim is reading Chainmail. It becomes apparent why the thief has these abilities. Chainmail was a wargame from 1971 onto which Gary Gygax attached some fantasy rules. Possibly the first such rules for any wargame. There aremany sections of original 1975 D&D that say ‘refer to Chainmail’ and as Jim’s reading it, for the first time in 30 years, he says “holy shit we never played with any of this. No wonder we had to houserule everything.” Here are rules for parrying and weapon speeds. The fighter (actually, “fighting-man”), wizard (actually “magic-user”), and cleric (strangely just cleric, not actually “god-botherer”) used all these rules. The thief didn’t exist in Chainmail and therefore the designers…well, Gary and Dave, invented all this stuff for him.

Now it becomes evident why so many groups played so different from each other and spent most of their time making new rules to fill in the gaps. Many of them, maybe most of them, didn’t have Chainmail. Gary et al had all this connective tissue, the ligament and cartilage from Chainmail. Everyone else, lacking this, had to make stuff up. Certainly, being the first RPG, a LOT of stuff was going to get house-ruled no matter what, but many players were just using these books and didn’t know what Chainmail was.

In the absence of the Chainmail foundation, house rules were created. Lots of em, and now not only was each group playing different from every other group, they were all playing different than the guys atTSR who DID have Chainmail . This explains a lot of the attitude Gary had back then. He often wrote that people were playing his game weird and this seemed to vex him. Yes, he used house-rules, that’s obvious from reading his shit, but people like Jim were using more house-rules than actual rules!

I’ve often noticed a difference between RPG gamers and wargamers. RPG gamers tend to argue a lot at the table about the rules, holding up play. Wargamers will argue for a little while, and then roll dice to determine which interpretation of the rules to use and work out the right answer after the game. Certainly there are a lot of differences between the two types of games and the people who play them, but looking back and considering how much of gaming is tradition passed on from player to player rather than rulebook to player, I wonder if part of this might not arise from the fact that wargames are foundation and the players argue about the high-level stuff. Whereas the original RPG was only the high level stuff and players weren’t using Chainmail, the foundation.

Jim’s reading Chainmail and we’re making our mans. First thing I noticed; your entire character can fit on a 3×5 card. There were stats for things like Bending Bars (barred doors and windows presumably) and lifting gates, but Jim made these rolls for us. So we didn’t put them on our sheet. Making a dude only took a few minutes because apart from your stats, there wasn’t anything to do! No choice to make. We all had enough gold to buy all the armor and weapons we could possibly use.

This meant that apart from your stats, all first level fighters were essentially the same. Same on the character sheet, same options in combat. Of course they would be, this is literally only one step removed from a wargame in which all mans of a given type are literally identical. Magic-users and clerics could choose different spells, but each only one.

We’re also using the “new” rules for hit points in which the fighters get a d8 and the thief and wizard a d4. ![]() Therefore Duncan the Thief is walking around with 3 hp. But so what? That’s how the game was played. Jim busts out his overland map, also over 30 years old, and shows us where we’re starting. A small town which he realized he named Banchory and mispronounced Bastenchury for 10 years. No thought is given to how we know each other. We agree to set out to the mountains in the northeast and kill the goblins who’ve taken over the old dwarven stronghold long-since ruined. There’s a bounty on goblin ears and we aim to collect!

Therefore Duncan the Thief is walking around with 3 hp. But so what? That’s how the game was played. Jim busts out his overland map, also over 30 years old, and shows us where we’re starting. A small town which he realized he named Banchory and mispronounced Bastenchury for 10 years. No thought is given to how we know each other. We agree to set out to the mountains in the northeast and kill the goblins who’ve taken over the old dwarven stronghold long-since ruined. There’s a bounty on goblin ears and we aim to collect!

We bust out the tact-tiles and Jim busts out the minis. These are real, actual minis from 1975. From Kreigspeil’s Middle-earth line. We’re playing with 32-year old painted lead.

From here on out, the process of playing is not entirely unlike the process of playing any other edition at 1st level. We all suck. None of us can fight worth a damn. Mark shows up about halfway through and now we have two fighters. Well, after we meet his character who’s been lashed to a pole and is being roasted by Orcs over an open flame. The new character introduced in the middle of the game is always in the next room, held captive by the bad guys. Thus it was handed down to us from olden times.

By the time Mark’s new character is ready, Dave’s magic user has been a slimy toad for half an hour, with another half an hour to go. He read a cursed scroll and there you are. “This is not fun” Dave reasonably states, but that’s the game. As Jim points out, “hey, if you don’t like it, I got another 10 guys waiting to play in this game.” It’s 1975 and the rules say “best for between 4 and 40 players.” Jim knew of many games that had dozens of players, though also many GMs.

It dawned on me at this point why Jim was always so surprised at the way we played D&D. Each player with one character. These days, one character is enough to manage. Back then, there were several factors pushing you toward running several characters at once. Each character could fit on a 3 x 5 card. No single character was worth a damn at low levels. If you wanted more than one thing to do in combat, you needed two dudes! Forget the fact that the magic-user got one spell for the whole combat, and the fighter gets to swing his sword as often as he wants, each had only that one option.

So your character was built on very little data, you had no options in combat, and you were very likely to die. 3 hit points! One hit took me down.

The rules themselves were barely there. You had to make it all up. This put so much responsibility on the GM. He had to be entertaining, imaginative, fair, rational. In many ways the steady march away from original D&D has been a sustained effort to remove the effects of a bad GM on the game. The more game elements are objectively determined, written down in books, the less you have to rely on the GM. The less you need a really good GM to run the game. And yes, the more of a science it becomes, and less of an art. Running this game was an art form and only a few people could do it really well. There’s something magical about that. Newer versions become more systematized and therefore more people can play. Mediocre GMs can run good games. But, if I’m being honest with myself, something of the magic is lost. That feeling that most of this game lived in your mind. Because of that, I think, it was more real. As more and more of the game lived in the rules and on character sheets, it became a game instead of a world in your head.

There were some rules I was surprised by. The rules for Parrying, for instance, which gave people an interesting choice in combat. Frankly, I thought these were the best parry rules I’d ever seen. Hell, they’re the ONLY parry rules I’ve ever seen that made sense! When designing the CODA system at Decipher to be used in the Star Trek and Lord of the Rings RPGs, my boss and I talked about a parry option and how we’d never seen a good one in an RPG and we decided such a thing was not possible (I was much younger then). “Either Parry is free, in which case you’d always do it regardless of how effective it was, or it’s a choice: Parry or Attack. And given such a choice, ‘damage or push’ why would you choose to push?”

Well here smaller weapons were faster. So fast that some rounds you get to attack twice. And on those rounds, you could parry your enemy AND attack! It was simple, and it worked. Simple to understand, simple in execution. I always understood the premise behind the weapon speed rules we never used in AD&D, but now I saw the OTHER rules they worked with to make them useful and meaningful. 32 year old game, still has something to teach.

By the end of that cold November night in 1975, I’d been dead for half an hour and was playing Patapon, a game from the future while the rest of the part was slowly killed. Total Party Kill. Turned out, we weren’t the only ones hunting the goblins. Orcs were also in on the hunt and we took a wrong turn and fought the Orcs first. Orc minis, also from 1975.

I would play this game again. Like Christopher Reeve in Somewhere In Time, I’d have to transport myself back 32 years. Consciously decide to put aside 32 years of gaming and put myself in that mindset. You have to put aside systems and character options and customization, but in exchange you get magic. The kind of magic that turns a hex-map and lead into a world you believe in and want to go back to.

Jim would run the game too and I’m not certain we won’t switch back and forth between 4E and…0E. But one thing I know, we’d have to meditate before each session. Return to that time, and put aside all desire to return to the future. The normal creep toward systems and objective rules, the very pressure that created AD&D and its children, would have to be disavowed. That’s not why we come to this. Each house rule would have to be examined to make sure it didn’t feel like a modern rule, a system. Because otherwise, why play this game? We have systems. But we want magic.

You can buy PDFs of these books online. Cheap. Absolutely worth it just to spend a hour reading the rules. You’re reading the blueprint for all of fantasy gaming right there. A direct and unbroken line leading from Dungeons & Dragons to Mass Effect and World of Warcraft. All one.

My first novel

My first novel My new novel.

My new novel.