After wrapping Prometheus, Ridley Scott announced he’s planning on revising his other masterpiece. I think he’s doing this because he’s old, and the attention he gets when he goes back to these old properties is much more satisfying to him than the attention he doesn’t get doing completely forgettable stuff like Robin Hood. But I, like a lot of people, am skeptical. I’m skeptical not because of Scott now, but because of how Blade Runner was made then. It is a unique film. The kind you only get when very unusual things happen during the production of your film. Without those unique elements, we’d not have the film we have. A film that prompts people to write essays about minor characters. A film worth examining again.

The Acid Test

Blade Runner opens with what I consider the canonical acid test shot. The answer to the question, “will I like this movie?” is right there, in that first shot. A giant eye, whose eye you do not know, stares at you with some hell-like cityscape reflected in it.

In that moment, either you say “whoah” and look in wonder, or you say “what is that? What am I looking at? Who’s eye is that? What’s going on?” Many people had that second reaction. I had the first. I didn’t understand what was happening, but visually I was blown away.

This often comes up in my daily work. A lot of writing in video games is explaining things to people, but that’s not writing. That’s design. Writing is the process of creating tension. And sometimes, often, that’s artful.

The opening shot of Blade Runner is artful. It’s not literal. Often I write something, and my coworkers ask “Will this make sense to everyone?” And my response is often “It’s ok if it doesn’t make sense.”

That notion, that everything everyone says in a video game must be perfectly comprehensible to the player, is one reason so much dialog in video games is horrible.

Home Video

I saw Blade Runner in the theater, but it made no sense to me. I was too young. I fell in love with it on home video. I spent an entire summer watching it. I was watching it the way you read a comic. Looking at the same images over and over. Finding more, absorbing more. This is something I can’t imagine doing now, but when you’re a kid you can hyper-focus on something in a way you cannot as an adult. I had no sense of time passing, no concept of “wasting time,” I was perfectly happy to close the blinds, turn out the lights, and run the movie again. My own private screening room.

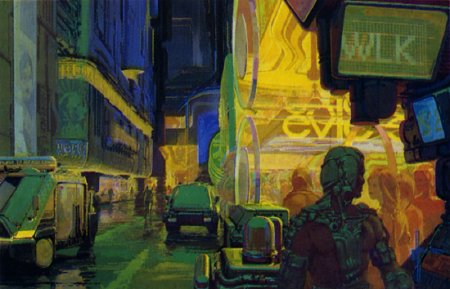

It may seem strange and, indeed, it is a little strange, but this was something you could do with Blade Runner that you couldn’t do with any other movie. It contained a level of detail unseen in any film before. It was richly layered. The sheer scale of what you’re seeing is almost unfathomable. The costume design of the people on the street was done by several different artists, each representing a different class of person. The vehicles were designed, not just by artists, but by engineers. Syd Mead knew how his designs worked. The parking meters in Blade Runner have elaborate signs explaining how to use them and what will happen if you abuse them (they’ll shock you and kill you!) The magazines, which you never see, on the newsstands have covers and articles on the front imagined by the production designers.

There’s a reason this film has so much detail. There was a strike, and they script wasn’t done. So for several months the crew did nothing except design and build more detail into the set. This is a lesson to the generations inspired by Blade Runner. You can’t create something like this on a normal budget or a normal schedule. It takes something extraordinary.

Less Human Than Human

One reason I was responding so intensely to the film was that, sitting in my living room experiencing the movie over and over, I discovered there was a potent story in there. A story overwhelmed by the visuals and the worldbuilding, sure, but these replicants–more human than the humans in the movie–and Deckard’s chase to kill them, is emotionally effective.

In the film, Rick Deckard is a Blade Runner, a term Scott borrowed from a completely different book. Blade Runners hunt down replicants, biological androids. Replicants are illegal on Earth, and that very statement tells us that there IS a somewhere else, the rest of the Solar System out there with human beings on it. Before we ever hear about the “Off-world Colonies” we know they exist.

Deckard hunts down the replicants one by one until the end and a long, bloody confrontation with their leader, Roy Batty. Throughout this process we watch as Deckard becomes more human. That’s what the movie is about. Deckard is just a machine when we meet him. Someone with a job and he does that job unthinkingly. It’s this last assignment that changes everything. He meets a girl who has an effect on him, and turns out to be a replicant herself, though she doesn’t know it. Deckard finds himself confronting her cruelly about her past, or lack thereof, and afterwards regrets it. Regret, over hurting what he’s previously looked at as a glorified toaster. It is this confrontation with a robot who believes she’s a human, whom Deckard believed was a human at first, that starts his journey.

When he kills the first of the renegade replicants, Zhora, he feels like shit afterwards. “The report would read: ‘routine retirement of a replicant.’ That didn’t make me feel any better about shooting a woman in the back.” He’s changing, seeing these things as people.

After the confrontation with Roy on the rooftops, Deckard’s made an important transition. Throughout the movie we’ve felt much more for the replicants than the humans. The replicants are desperate and alone and afraid and confused. Confronting their own mortality. Watching Zhora trying desperately to escape, watching Pris and Roy with J.F. Sebastian, you’re filled with compassion for these people.

At the end, watching Roy die, we feel for Deckard for the first time. Feel compassion for him, because he’s stopped being a mindless bureaucrat and started feeling like a human being for the first time.

The film is dense and confusing and some of it, frankly, doesn’t make a lot of sense. Ford famously complained that he played a detective who didn’t do any detecting and that’s exactly how it felt watching it. Zhora is really the only replicant he finds himself, the rest find him or draw him to them. There are lots of glaring ADR problems and cut corners that you don’t need to watch 100 times over the course of one summer to notice.

But in spite of this, on repeated viewing, the story of Deckard becoming human through the act of hunting these replicants, is deeply resonant. Before, Deckard is living in the Waste Land, living inauthentically. By the end he’s a human being again. That’s something the replicants gave him; something Roy Batty gave him.

Pauline Kael said you would probably not like this movie, but your toaster would love it. She felt it lacked emotion. Given how overwhelming the visuals are, how utterly different the world Scott and his team created is from anything Kael or anyone else had seen before, it’s easy to understand how she failed to see the human story here. Failed to notice the brilliant acting on the part of Rutger Hauer, Brion James, and Darryl Hannah, playing creatures who are at once impossibly strong and capable physically and at the same time emotional children, exploring the world for the first time, fearing for their own mortality, not understanding it.

Those elements are there, however, and once you’ve let the visuals sink in, once you start taking them for granted, you can see the human story in here. Watch Pris try and lure J.F. Sebastian in. She’s being manipulative, but in a very crude manner. She’s not entirely comfortable with her role as a “pleasure model” and hasn’t figured out how people work yet. She’s not sure her plan to meet him and get him to trust her will work and when it begins to fail and her attempts to keep the conversation going led nowhere, she resorts to instinct. “I’m hungry, J.F.” she says, and I think she’s being honest.

Honesty works, and Sebastian leads her in to his hideaway.

Watch Leon in Chu’s Eyeball Palace, or whatever it was called. Putting his hand into the freezing cryoliquid, pulling it out and smelling it. He’s exploring, experiencing, curious. He’s not an unfeeling, unthinking killing machine.

Finally, watch Batty kill his creator. The fear and pain and terror flashing across his face as he does so. And then watch him ride the elevator down afterward, thinking about what he’s just done, and then thinking about thinking about it as his face contorts into a frown. Not a lot of actors can do that, convey these conflicting emotions without dialog, and not a lot of stories call for it.

Ready contemporary reviews of the movie, I was struck by something. The future Blade Runner presents isn’t supposed to be appealing. It’s supposed to look run down, full of trash. It’s meant to be bleak and, for many reviewers, that’s exactly what it was. It’s a dystopian vision of the future, maybe the distopian future in film. They mostly hated it, called it cynical or nihilistic, the same language they used describing John Carpenter’s The Thing which came out the same year.

Yet, in spite of this, I fell in love with it. It seems like if you were an adult when it came out, this vision of the future was bleak. But if you were a kid, it was exciting. Ridley Scott transmitted one message to the adults watching, and a completely different message to us kids.

Phillip K. Dick didn’t like what Scott did to the replicants, the way Scott described them to Dick, he made them sound in all ways superior to human beings. But Dick didn’t live to see the film. I think if he had, he’d have realized he was wrong. In both the book and the movie, Deckard is an automaton, going through the motions, unthinking, unfeeling. In the movie, the replicants–while not human–are experiencing life the way a human being does, the way a human being should, the way Deckard does not. Until the end when Roy dies. I think that’s exactly what Dick wanted.

Until 1992, and the advent of the Workprint, I thought Blade Runner was something only I got. There was no internet, I thought everyone else had overlooked this movie. I was wrong. There’s an entire generation of people exactly like me with exactly the same experiences. It was the discovery of the Workprint that made this clear.

The Workprint

Back in the day, before the twitter and reddit, there were, like, newspapers and shit and it was reading the L.A. Times that I learned about the Workprint of Blade Runner.

Back in the day, before the twitter and reddit, there were, like, newspapers and shit and it was reading the L.A. Times that I learned about the Workprint of Blade Runner.

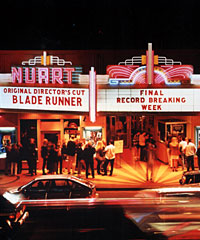

Some friends of mine and I drove up to L.A. to watch it at the Nuart. The Nuart is a classic place to see art films and the fact that Blade Runner in any capacity was playing here meant that something special was happening. When I saw the temp opening credits and heard the temp score, I felt like I was part of movie history. The theater was packed full of college students like me and people from the industry who wanted to see the original print of the movie that influenced a generation.

It was an amazing experience. It was, to someone who had memorized the original, radically different, almost every scene had something different in it. Bryant describing Leon as a loader on intergalactic freighter, “the only way to hurt him, is to kill him.” Rachael whispers “Deckard” to him in the elevator causing him to spin and whip out his gun. Lots of little differences.

In June of that year, Kenneth Turan, film critic for the L.A. Times, wrote a great article about the history of the film called Blade Runner II in which he agreed with all those who felt the film was better without the voice over, but added “Face it, the only reason we can appreciate this version is because we’ve all seen the version with the voice over and know what’s going on.”

At the time, this was not called “The Workprint” it was called “The Director’s Cut” and was, to my certain knowledge, the first time anyone had ever used that term.

Scott eventually came out and said “No, that’s not my cut of the film, that’s the workprint. THIS is my original cut of the film…” and the Director’s Cut was released in theaters. I got to see it in 70mm at a theater in Long Beach and while the experience was astonishing…at least equal to seeing Lawrence of Arabia or 2001 on the big screen…this actual version of the movie wasn’t that different from the theatrical release. Sure, there was no voice-over, there was no happy ending, and there was the Unicorn Sequence, but apart from that, it was essentially the same. Nothing like as radical a departure as the Workprint.

When I got a DVD player in 1997, this and the Fifth Element were the first movies I bought. As with Laser Disc before it, Blade Runner was the movie people used to take the new digital format for a spin. Put it through it’s paces. See how much better it could look than video tape. It was the Dark Side of the Moon of digital video players.

DVD

I learned about the 5-disc edition of the film somewhere around 2001, when it was originally timed to come out to mark the 20th anniversary of the original. But problems securing the rights prevented its release. In the meantime, we got a pretty good documentary from the BBC: On The Edge of Blade Runner.

Finally, the 5 disc “Ultimate Edition” came out, and something was restored to me which had been long lost. The original theatrical release of the film.

Until this edition came out, the film was dead to me. I couldn’t watch the Director’s cut. It was too sterile, bleak. It’s amazing, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not my Blade Runner.

The 5-disc edition is as comprehensive a document of a film as you’re ever likely to see. I’ve dug into it for about 10 hours and still haven’t exhausted all of its content. One thing we get here is Harrison Ford talking about the movie for the first time.

I’d long come to grips with the fact that in no interview, in no career retrospective, would Ford discuss this movie. I didn’t know precisely why, but obviously it was something he wanted to forget about. I was delighted to learn that he was involved in this version, though, and he speaks very charitably about the film. This is a guy who’s not afraid to call someone on their shit, as he does in the documentaries included with Star Wars. Here, he speaks with working with Scott, Scott speaks about working with him, and all the actors talk about working with both. I feel as though if you watch the special features and read between the lines, you get a pretty clear picture of why Ridley Scott and Harrison Ford didn’t get along.

Actorly Stuff

Edward James Olmos and Darryl Hannah and Rutger Hauer all did a lot of actorly stuff, they fleshed out their characters and brought ideas to Ridley. Ridley seems to respond well to this. Even some pretty goofy stuff that Hauer wanted to try, Ridley would go with it. The actors, and Ridley, speak very positively about this experience. Scott seems to get genuinely excited when actors come to him with ideas. “Ridley, what do you think of this?”

Whereas Ford would go to Ridley and ask “So who is this guy I’m playing?” Ford wanted Scott to engage with him, tell him who Deckard was, give him direction. Ridley’s reaction to this seems to be “This is what I pay you for. You’re an actor, you figure it out. I have a movie to make.”

It’s difficult, looking at the depth and breadth of Scott’s vision, to disagree with him. This is not an intimate character drama, this is little more than the creation, whole cloth, of an entirely new world, never before seen on screen.

Ford has long been saddled with the accusation that he hated the idea of the voiceover, and so deliberately did a bad job so as to sabotage it. This is a story propagated by Katherine Haber, the production executive.

Listening to Ford tell the story, and listening to Scott talk about it, it’s clear to me this is not the case. Ford is a professional and did his best, but the writing of the narration was tortured and this, I believe, is what’s coming through Ford’s performance.

“These Cups Suck”

There’s a great moment where the production designer is watching one of his team go to Scott with two different coffee cups and ask the director which cup should be used in the scene with Leon and Holden. And Scott’s reply is “these both suck, get some more.”

The guy with the cups was pissed. What was wrong with THESE cups, if these weren’t good, which ones SHOULD he get? The Production Designer saw this and went to his man and said “Listen dude, this isn’t how Ridley works. Go get A HUNDRED cups. What do you care? It’s not your money, go buy a shitton of cups and let Ridley pick the one he wants.”

Ridley did a lot of takes and at one point in the documentary included in this edition, Dangerous Days, we see several, like 12 takes of a close-up of a hand depositing a bowl of rice and shrimp on the table. 12 takes of a 3 second shot. At that point, it’s clear he’s sending a message to the money men breathing down his neck. “Look what I can do if you piss me off.”

Ridley did a lot of takes and at one point in the documentary included in this edition, Dangerous Days, we see several, like 12 takes of a close-up of a hand depositing a bowl of rice and shrimp on the table. 12 takes of a 3 second shot. At that point, it’s clear he’s sending a message to the money men breathing down his neck. “Look what I can do if you piss me off.”

Within the features of this edition, we get to see all the stuff they created for the movie, much of which we only catch glimpses of in the film. All that detail from months of work. The magazine covers they invented, the parking meters, everything. It’s breathtaking.

We get to see those bits of Roy’s speech at the end which they filmed, but cut out. “Reproduction, sex, love. The simple things. But no way to satisfy them. To be homesick with nowhere to go. Lots of little oversights.” When he says that last line, he’s got such a unique look of amused and compassionate melancholy on his face. We never hear him talk about his fears of death, about his life, to anyone in the movie except Deckard. When he dies, before he dies, he pours everything into Deckard. When you see the original speech in the script, it’s clear why it had to be cut down, but seeing some of this stuff they filmed but didn’t include makes me wonder if maybe they should have left it in.

We get to see those bits of Roy’s speech at the end which they filmed, but cut out. “Reproduction, sex, love. The simple things. But no way to satisfy them. To be homesick with nowhere to go. Lots of little oversights.” When he says that last line, he’s got such a unique look of amused and compassionate melancholy on his face. We never hear him talk about his fears of death, about his life, to anyone in the movie except Deckard. When he dies, before he dies, he pours everything into Deckard. When you see the original speech in the script, it’s clear why it had to be cut down, but seeing some of this stuff they filmed but didn’t include makes me wonder if maybe they should have left it in.

All the deleted scenes, a lot of the unused narration, and even an alternate opening title we’ve never seen, are all compiled and cut together making a 30 minute alternate version of Blade Runner that’s simply fascinating. The unused narration is sufficiently awful to warrant cutting it. Great to hear though.

“All I Could Do…”

One great delight of this edition is getting to watch other directors talk about the movie, people like Guillermo Del Toro and Frank Darabont. I have to agree with Del Toro; the voice over is part of my Blade Runner. I like the voice over. Yes, Darabont is correct, the great crescendo reached in Batty’s death on the rooftop is diminished by Ford saying “maybe he loved life more than anything else. His life, my life.” Yes, that’s a needless restatement of what we just saw. We got it, we didn’t need anyone to explain it. But I feel it’s worth it, necessary, for the shot of Deckard in slow motion, the rain pouring down his face, and the statement; “All I could do was sit there and watch him die.”

Because that sentence shows us Deckard completing his journey. Before that, he was in the Waste Land, living the life inauthentically led. But Batty’s death awakens him to the reality of his own humanity. And it’s not ham-fisted, he doesn’t say “I realized that he was more human than I ever was” or anything like that. It’s up to us to realize that “All I could do was sit there and watch him die” means “I realized that he was more human than me and now that I realize that I find myself wanting to save him, and powerless to do so.” Darabont passionately argues that the voice over ruins everything, but I disagree. I think the part he hates in that sequence, the artless, literal statement about Roy loving life, is the groundwork for the line that gives the entire movie meaning. “All I could do was sit there and watch him die.”

Is He Or Isn’t He?

One ongoing debate which Scott seems very interested in ending is the “is Deckard a replicant” issue. I believe that through watching Scott talking about it now, and then, and listening to the comments on the DVD from people close to him, that the truth can be ferreted out.

Darabont says “No! Deckard CAN’T be a replicant!” Because, of course, it would utterly destroy the emotional throughline of the film. And in this I believe he is correct. But he wasn’t involved in production. He’s just a fan, in this regard.

Scott says “I don’t know what I could do to make it more clear. If it isn’t obvious to you that Deckard is a replicant, you’re a moron.”

Mmm. I’m not sure it’s as clear as Scott would like it to be. I think, based on the stuff the people around him said, about what HE said during production, that Scott had no intention to make it clear that Deckard was a replicant. Scott’s goal was to raise the question. That’s what’s important. Keeping the audience off-guard. By raising the question, you create that Phillip K. Dick moment of getting the audience or the character to wonder “is EVERYTHING I know false?” That’s what so much of our SF in film in the last 30 years is based on. After the fact, 25 years later, Scott is very certain Deckard is a replicant, but I think he’s just interested in winning an argument. One of the scenes cut from the film shows Deckard and Rachael flying off into the sunset and talking.

Rachael asks if the two of them are now lovers. Deckard explains that yes, they are. She says this is the happiest she’s ever been. Then she ominously says;

“You know what I think?” she asks, looking at the scenery flying by.

Deckard waits for the answer.

She turns to him and says, with no romanticism in her voice; “I think you and I were made for each other.”

In another situation, this would be a romantic sentiment. But Deckard shoots her a look and realization dawns on his face.

Why was this cut? Why not use it? It’s a good scene, and necessary if Deckard is a replicant. I believe Scott cut it because he knew it answered a question he knew should NOT be answered. He knew the goal was to raise the question.

At least, he knew it 25 years ago. I think he got frustrated that, back then, no one thought to ask if Deckard was a replicant and now he’s gone over to the other side. Forgotten the point he was trying to make 20 years ago. Raising the question of Deckard as Replicant is more important than answering it. Keeping the audience off-guard. What is real?

Vangelis

One thing people underestimate is the impact of Vangelis’ music on the positive reception by the fans of the film. The people involved in the features on the DVD go to great lengths to credit him. “You know, Hampton,” David Peoples says, after Hampton Fancher talks about all the emotion and longing in the love scene with Deckard and Rachael being in the music, “a good writer doesn’t need the music.” Fancher, without missing a beat, says “Yeah, but good movies do.” I think Vangelis is almost as important to what makes Blade Runner, Blade Runner, as Ridley is.

It’s been 30 years since Blade Runner came out and inspired at least two generations of filmmaker. One thing that often disappoints me when I see a movie that’s clearly inspired by Blade Runner…like Renaissance or The Matrix, is that so many people steal the visuals and the ideas, but leave out the human story. Without that, without the emotional resonance of the doomed replicants and Deckard’s journey to humanity, without Rachael’s confusion and longing, none of us would have watched this film over and over again. It’s what makes this film meaningful beyond just the pretty pictures. It has weaknesses, but you cannot rightly accuse it of lacking emotion and human drama.

It’s too bad I can’t say it’s flawless…but then again, what is?

My first novel

My first novel My new novel.

My new novel.