The shortest unit of time in the multiverse is the New York Second, defined as the period of time between the traffic lights turning green and the cab behind you honking.

To me, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series is life-affirming. It’s fun, funny, dramatic, human, brisk, and full of heart. It’s nourishing. It is a vitamin for your soul.

So I’m always surprised to discover friends who not only don’t read the Disc, they have no idea it exists! Madness! I guess it’s a US/UK thing. For a while, before J.K. Rowling came along, 1% of all books sold in Britain were Discworld books. But he never exploded in America like I think he could have. Perhaps because of the America’s attitude toward his chosen genre.

Not Fantasy

They felt, in fact, tremendously bucked-up, which was how Lady Ramkin would almost certainly have put it and which was definitely several letters of the alphabet away from how they normally felt.

I’m not sure his American publisher ever knew what to do with him. He wrote fantasy, so stick him in the Fantasy section of the bookstore and market him like a Fantasy author.

I’m not sure his American publisher ever knew what to do with him. He wrote fantasy, so stick him in the Fantasy section of the bookstore and market him like a Fantasy author.

Certainly he wore the genre like a badge. When J.K. Rowling inexplicably came out and said she didn’t consider the Harry Potter books “fantasy,” because implicitly the genre is some kind of ghetto, Pratchett was the first and loudest to call her out on her bullshit. “I would have thought that the wizards, witches, trolls, and unicorns would have given her a clue? What does she think she is writing?!”

He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and became an outspoken advocate of the right to end your own life and so he got a ton of press from reporters otherwise unfamiliar with his work. They routinely challenged him on being a fantasy author. Why would someone choose to be that?

Pratchett never responded with anything other than bemused pity for people like J.K. Rowling who didn’t get it. Though I can understand her point of view.

Rowling famously bounced off The Lord of the Rings when she was young, picked up Narnia which she found problematic and why not, and concluded the genre was not for her. Fair enough. I’m surprised when people make it through The Lord of the Rings. It’s a very strange book and not at all a novel.

So she always felt like “fantasy” was this other thing. It seems like a lot of people feel that way. They try and read Lord of the Rings, they don’t get it, and they think “so this is fantasy.” LotR is certainly held up as an exemplar, so I understand why you’d think “if this isn’t for me, fantasy isn’t for me.”

I think this impression is reinforced by the popularity of George R.R. Martin’s War of the Roses fanfic, A Song of Ice and Fire aka Game of Frones. He took traditional fantasy, married it to classic soap opera plotting (basically doing the same thing to Fantasy that Chris Claremont did with superheroes during his legendary X-Men run) threw in a lot of sexual violence and people who don’t habitually read fantasy thought “My god, I didn’t know fantasy could be like this! IMPORTANT PEOPLE DIE ALL THE TIME!”

Well, I can’t argue with that! Neither can 1970’s Michael Moorcock or 1980’s Glen Cook, but I don’t think enough characters got their genitals mutilated for either Elric or The Black Company to become mass-market products. Let that be a lesson to you, aspiring writer! I’ve seen many people openly declare Martin’s work isn’t really Fantasy.

But to me, it’s Pratchett who doesn’t belong in the genre. Not because the genre is any kind of ghetto, it would be ridiculous for me of all people to suggest this. But because with one or two exceptions, his plots were never fantasy plots.

Fantasy

The people of Ankh-Morpork had a straightforward, no-nonsense approach to entertainment, and while they were looking forward to seeing a dragon slain, they’d be happy to settle instead for seeing someone being baked alive in his own armour. You didn’t get the chance every day to see someone baked alive in their own armour. It would be something for the children to remember.

Stephen R. Donaldson said the difference between fantasy and literary fiction was that in literary fiction the characters are expressions of their world, whereas in fantasy the world is an expression of the characters.

Stephen R. Donaldson said the difference between fantasy and literary fiction was that in literary fiction the characters are expressions of their world, whereas in fantasy the world is an expression of the characters.

He was absolutely correct, though I’m not sure anyone was paying attention. I think by and large fantasy readers come to the genre because they want an adventure. If it’s epic fantasy, they want to see the world at stake. They want a magic talisman or two, a classical hero of whatever gender, possibly a Hidden Monarch or Prophesized Chosen One, and it would be nice if the stakes were crazy high.

If it’s gritty fantasy they want hardbitten cynical heroes slogging through the underbelly of a dark city, on whose mean streets a million stories can be told. They want the author to trick them into thinking the book has a ‘magic system’ with rules the characters all know and obey. You get it.

But Pratchett rarely, and only in his early work, every worried about these things. In fact if there’s a genre Pratchett reminds me of, it’s the mystery genre.

Mystery

“Now I know you ain’t the Ghost…so what are you, to be sneaking around in places where you shouldn’t be?”

Andre gave Granny a long look, like a man weighing up his chances.

“I…hang around in dark places looking for trouble,” he said.

“Really? There’s a nasty name for people like that,” snapped Granny.

“Yes,” said Andre. “’Policeman.”

People who don’t read mysteries think that people who do, come for the mystery. The classical Agatha Christie plot where the whole book is like a crossword puzzle and if only you were smart enough you could figure out whodunit.

But with few exceptions (I mean, those books and those readers do exist) people come to the fantasy genre for the characters. They love and want to spend time with Dalziel and Pascoe, Morse and Lewis, Kinsey Milhone, Bill Slider, or Spenser (you can tell exactly when I started reading mysteries by that list). It doesn’t really matter what those characters are doing, we just like them. We want to hang out with them.

That’s the kind of fantasy Pratchett wrote. He wrote characters you love and identify with and then he layered on top of that something that raised him above the rest. He wrote about the human condition in a manner so honest and revealing I can think of no one like him but P.G. Wodehouse and Kurt Vonnegut. Like Alan Coren who influenced him hugely, he believed in the fundamental comedy of a person who takes themselves seriously. Pratchett knew as much about the inner workings of the human soul as Raymond Chandler, but where that knowledge beats Philip Marlowe down, making him a cynic with a heart of gold, Pratchett’s characters are never defeated. There’s a kind of Buddhist celebration in the pain and suffering in the world. “Look how venal and cruel and capricious and loving and caring people are,” Pratchett says. “Isn’t it wonderful!?”

Yes! It is! Thank God someone had the sense to say it! That’s why I felt I had to write about Pratchett. Several of my favorite authors recently passed away. Robert B. Parker and Iain M. Banks were particular blows to me. But I didn’t write 7,000 words on either of them. Why?

Pratchett

There are few authors who had as big an impact on me as Terry Pratchett. T. H. White, certainly. I learned a lot about morality and love and justice from The Once and Future King. Growing up the only son of a single mother, Robert B. Parker’s Spenser taught me a lot about masculinity and what it meant to be a man.

There are few authors who had as big an impact on me as Terry Pratchett. T. H. White, certainly. I learned a lot about morality and love and justice from The Once and Future King. Growing up the only son of a single mother, Robert B. Parker’s Spenser taught me a lot about masculinity and what it meant to be a man.

But Terry Pratchett taught me an arguably more important lesson. He taught me to imagine people complexly. Pratchett, like Douglas Adams before him, did not deal well in relationships. I always got the sense that Pratchett found intimacy difficult to write about. There is an almost complete lack of it in his books.

What there is, instead, is a deep understanding of the inner workings of the human mind. A sense of the basic alienation we all experience. We are all alone inside our heads, and we lead complex inner lives with ambitions and fears and certainties and doubts, all competing, sometimes in contradiction.

Adams

In 1986 it was not unusual for a fellow fantasy fan to recommend Pratchett as “like Douglas Adams, but Fantasy.” Yep. That was true. Back then. Observe:

Adams;

Motionless the alien ships hung, huge, heavy, steady in the sky, a blasphemy against nature. The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don’t.

Pratchett;

Sunlight poured like molten gold across the sleeping landscape. (Not precisely, of course. Trees didn’t burst into flame, people didn’t suddenly become very rich and extremely dead, and the seas didn’t flash into steam. A better simile, in fact, would be ‘not like molten gold.’)

After a few years, you really couldn’t make that comparison anymore. For one thing, I never got the sense that Douglas Adams was a novelist. Like. . .he didn’t want to be a novelist, he didn’t like being a novelist, and he avoided it as much as possible.

He was a comedy writer. He wrote comedy for radio and TV and when the opportunity came to adapt his work into print, he went along with it because why not? But The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy wasn’t born a book. It started on episodic radio and once you know about that tradition, you see it everywhere in the work.

Whereas Pratchett only ever wanted to be a novelist. As far as I know, he never tried to write a screenplay, or a sitcom. They are wildly different writers with profoundly different worldviews.

For Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was an exercise in misanthropy and cynicism. Everyone Arthur Dent meets is desperately trying to seem cool, and the more you know them the more you realize how unhappy they all are. No one ends up together, nothing has any meaning. That’s how Adams saw the world.

But for Terry Pratchett that aloneness might lead one to behave selfishly, but this could be overcome. Indeed, the great persistent theme of the Discworld is that “personal isn’t the same as important.” He developed the theme so well, he eventually developed a main character who could transcend that philosophy and move on to something better. You got the sense, reading Terry, that you were growing with him as a person.

It was a theme that emerged over time, it didn’t spring from the first book fully developed. If you start with the first Discworld novel (do not start with the first Discworld novel) you find an able writer enjoying making fun of classic fantasy.

Discworld

Longbows weren’t encouraged in the city, since the heft and throw of an arrow could send it through an innocent bystander a hundred yards away instead of the innocent bystander at whom it was aimed.

Eventually, and critically, Pratchett’s fantasy setting The Discworld became a deliberate mirror of our own. No other fantasy series does this, and Pratchett didn’t do it by accident.

In an almost science-fiction sense, he created another world because he wanted to talk about ours, wanted to share his experience with this world, all the things he’d read and learned and which he believed you’d love. Like Tim Powers, Pratchett did a crazy amount of research and like Powers often the most fantastical and whimsical elements of a story were the ones he ripped off from the real world!

Characters in the later books quote people from our world all the time, often twisting the quotes around in humorous ways such that you had to be in on the joke to get it, which was half the fun. Pratchett mines so much of our culture and history, I doubt any single reader (including myself) has ever detected every reference.

The first Discworld novel was published in 1983 when Terry was 35. He’d done other stuff—fantasy novels with some science-fiction elements in—and he’d toyed around with the idea of a flat planet and how it might work, but it’s the first couple of Discworld books that present it as a fully-developed world. The round, flat planet carried on the backs of four elephants who are all standing on the back of a giant sea turtle, swimming through space.

Color and Light

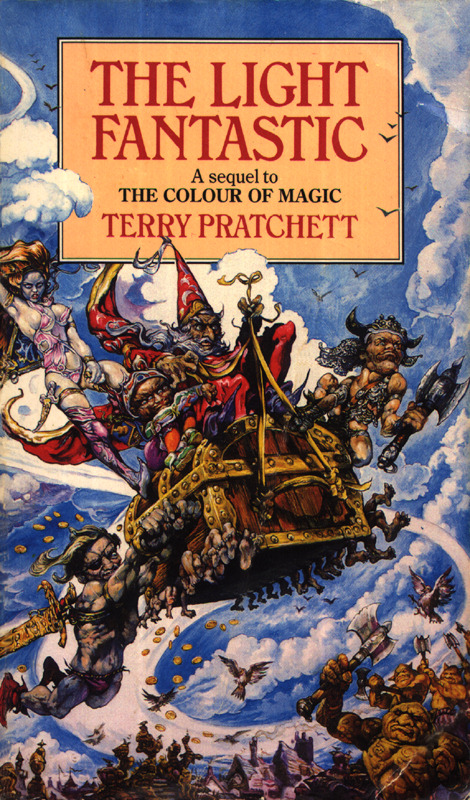

The first two books, The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic are not representative of where the Discworld would go. They’re relatively straightforward Pulp Fantasy pastiches. Each book is a tour of famous tropes and thinly disguised characters from fantasy. Specifically the fantasy that was popular in the 1960s and ‘70s. Conan, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. The Pern books are lampooned in there. I think a lot of these references would baffle a new reader today.

The first two books, The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic are not representative of where the Discworld would go. They’re relatively straightforward Pulp Fantasy pastiches. Each book is a tour of famous tropes and thinly disguised characters from fantasy. Specifically the fantasy that was popular in the 1960s and ‘70s. Conan, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. The Pern books are lampooned in there. I think a lot of these references would baffle a new reader today.

The main character in these books is someone I think Pratchett felt burdened with later. Like a long-established rock band that feels duty-bound to its fans to trot out the old classics, Terry would go back to Rincewind, but I often wondered if that was mostly because the older fans clamored for it.

If complete and utter chaos was lightning, then he’d be the sort to stand on a hilltop in a thunderstorm wearing wet copper armour and shouting ‘All the gods are bastards!’

Rincewind is a hapless wizard who only ever learned one spell, but like the spells from Jack Vance’s Dying Earth books, the spell Rincewind knows has a mind of its own, and lives in his head trying to get out.

His constant companion is Twoflower the Disc’s first Tourist (and now you know where that Nethack reference came from. Unless, as is far more likely, you have no idea what Nethack is).

Twoflower is an insurance salesman, giving Pratchett an opportunity to be funny and comment on human nature. When the proprietor of the Broken Drum (‘you can’t beat it’) Tavern figures out what insurance is, he immediately takes out a policy and then burns his own inn down to collect.

Rincewind is Pratchett’s Arthur Dent. In fact, I think Dent’s existence gave Pratchett permission to write Rincewind. Where Dent is hapless and disaffected, Rincewind is an explicit and self-avowed coward!

And like Adams’ hero, Rincewind is not going to get the girl. The difference here is that Adams seemed to be writing people he knew. Trillian impresses me as an amalgam of women Adams met at a certain period of his life.

When Rincewind meets a girl, on the other hand, she’s a barbarian princess who looks like a Frazetta drawing. Of course she does, that’s what Pratchett was parodying. But at the same time, there’s some commentary there. Adams wrote the girls he couldn’t connect with into his book with a hero who can’t connect to them. Pratchett wrote the girls he met in fantasy novels but could never imagine being with, and stuck them into his fantasy novel with a hero who can’t ever be with them.

“My name is immaterial,” she said.

“That’s a pretty name,” said Rincewind.

It was easy, back then, to imagine Rincewind as an author substitute the way it seemed Arthur Dent was for Douglas Adams. But I don’t think that was ever true. I think, inasmuch as Spenser is a HIGHLY idealized version of Robert B. Parker, it’s Sam Vimes who’s Pratchett’s idealized version of himself.

It was easy, back then, to imagine Rincewind as an author substitute the way it seemed Arthur Dent was for Douglas Adams. But I don’t think that was ever true. I think, inasmuch as Spenser is a HIGHLY idealized version of Robert B. Parker, it’s Sam Vimes who’s Pratchett’s idealized version of himself.

While Pratchett would eventually dump Rincewind for more interesting characters like Vimes, characters with depth to support stories with depth, he never really got away from his inability to write intimacy in relationships. Vimes ends up married and happy, but in a very pragmatic way. No romance.

But surely that must be MY hypocrisy! I praise the man for the way he wrote the human condition, then criticize him for not giving us an idealized emotional relationship? I call bullshit on myself!

Pratchett would argue “Vimes and Sybil are happy together!”

And my response would be: “Yeah but they each. . .settle for the other. There’s no spark, no fire. It’s so pragmatic.”

“Yes!” I imagine Pratchett saying. “Just like everything else in life! Weren’t you paying attention to what I was writing before?”

Good point. I am properly chastised, Imaginary Terry Pratchett!

These are terrible books to start with. If you hear all this great stuff about Pratchett as a writer, and then read those first two books, you’ll leave scratching your head wondering what all the fuss is about. Fans often say ‘you have to start at the beginning’ but that assumes someone’s going to just read all 40 books. Don’t listen to hardcore fans, they lack perspective. That’s what defines ‘hard core fan.’ It’s the reason I had no idea if the first X-Men movie was any good.

So you can skip these and come back around to them if you’re hooked and run out.

Sourcery and Rites

He had the kind of deep tan that rich people spent ages trying to achieve with expensive holidays and bits of tinfoil, when really all you need to do to obtain one is work your arse off in the open air every day.

With his next couple of books, Equal Rites and Sourcery you see Pratchett starting to use the Disc to tell stories. To put his ideas about the world on paper, rather than just make affectionate fun of 70s fantasy.

Equal Rites introduces us to Esk, a girl who was born to be a wizard, in a world where all wizards are necessarily (?) men. The topic of gender roles and woman’s place in the world becomes more and more relevant with each passing year and Pratchett never shied away from tackling it head on.

“And what are you doing on it, I would like to know? Running away from home, yesno? If you were a boy I’d say are you going to seek your fortune.”

“Can’t girls seek their fortune?”

“I think they’re supposed to seek a boy with a fortune,” said the man, and gave a 200-carat grin.

30 years before anyone thought to vote brigade the Hugos because authors dared write about something other than Hard Men making Hard Decisions, Pratchett was very successfully writing about being a girl in a boy’s world. In spite of writing some of the best female characters in all fiction, I don’t remember anyone ever asking Terry “why do you write such strong women?”

I think that’s because he had more in common with Howard Hawks than Joss Whedon. Whedon’s women show us a mostly male version of the female fantasy. A strong woman is one who can fight vampires! Fight the Hulk! Fight the Stereotype!

I think that’s because he had more in common with Howard Hawks than Joss Whedon. Whedon’s women show us a mostly male version of the female fantasy. A strong woman is one who can fight vampires! Fight the Hulk! Fight the Stereotype!

And certainly our culture needs that counterpoint to the male version of the male fantasy. But it’s also ok, and I think more important, for a “strong character” to be strong without having to shoot a gun or stake a vampire through the heart. We inherit those strengths from centuries of celebrating male virtues.

But Pratchett’s best character, the witch Tiffany Aching, never wants to be a wizard, it never occurs to her. She’s perfectly content being a woman in a woman’s world, and that’s ok. The Hawksian woman is strong, smart, capable, confident, but completely feminine. It would never occur to Angie Dickenson’s character in Rio Bravo to pick up a gun. Being good with a gun, being capable of and willing to kill people, is not the only virtue, and lacking those qualities is no vice. In spite of what 50 years of action movies and 300 years of patriarchy might have taught us to the contrary.

Rites also introduced a witch named Granny Weatherwax, but it’s not 100% the titanic character we’d meet later. Pratchett was working his shit out here, trying ideas and—like the idea of a flat world—would circle back around and develop characters and plots more fully in later books if he thought they deserved it.

A lot of Pratchett’s core ideas emerge here in one form or another and this isn’t a terrible place to start, but Granny Weatherwax changes so much by the next time we see her, I think it’s best to come back to this one to see where Granny started.

Sourcery is another Rincewind book and by this time I started to feel like the wheels were coming off the Rincewind wagon.

He did of course sometimes have people horribly tortured to death, but this was considered perfectly acceptable behaviour for a civic ruler and generally approved of by the overwhelming majority of citizens. The overwhelming majority of citizens being defined in this case as everyone not currently hanging upside down over a scorpion pit.

I mean, it’s funny! The early books are all funnier than the later books because I think Pratchett used humor as a gimmick and the better a writer he was, the less he needed it.

Trilogies

Pratchett would regularly create an entirely new cast of characters for a new book in a new setting, and see where it went. I suspect he knew, when he was writing Pyramids or Moving Pictures, or Small Gods that they would be one-offs, just as I suspect he knew his Big Four characters (Granny Weatherwax, Sam Vimes, Moist von Lipvig, and Tiffany Aching) were sophisticated enough to shoulder lots of stories.

But I noticed rereading all the books since Pratchett’s death six months ago, that each of these characters featured in what seemed to me to be distinct trilogies. There are many Granny Weatherwax books, for instance, but I think there are three core books where everything’s firing on all cylinders, and this is equally true for the other characters.

These then are my recommendations.

Wyrd Sisters

“‘Tis not right, a woman going into such places by herself,” he said.

Granny nodded. She thoroughly approved of such sentiments so long as there was, of course, no suggestion that they applied to her.

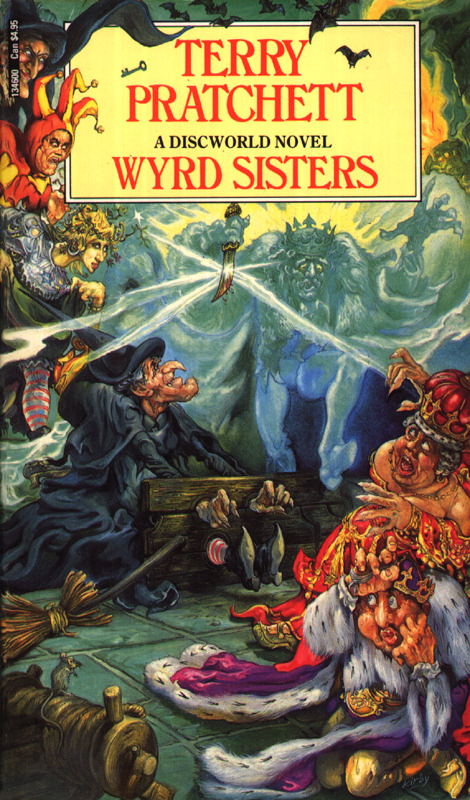

There are 40 Discworld books, I’m not going to cover them all, but by the 6th book, Wyrd Sisters, Terry had worked his shit out and produced a book that is a good place to start. Although I think there’s a better one, stay tuned.

There are 40 Discworld books, I’m not going to cover them all, but by the 6th book, Wyrd Sisters, Terry had worked his shit out and produced a book that is a good place to start. Although I think there’s a better one, stay tuned.

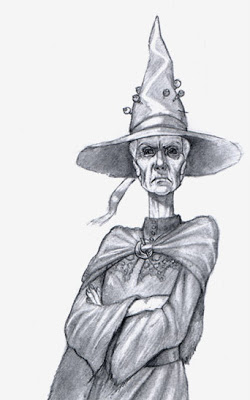

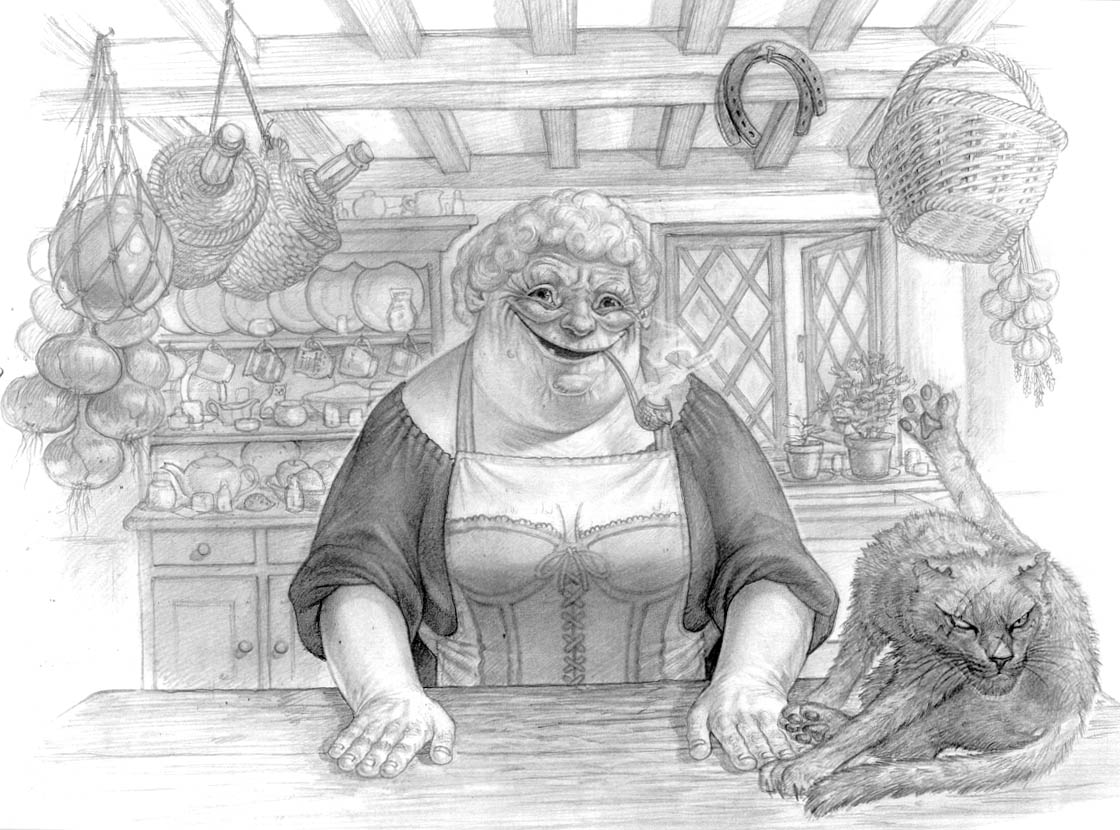

Wyrd Sisters introduces three witches: the Maiden, the Mother, and the Very Old Crone in the forms of Magrat the maiden, Nanny Ogg the mother, and the reappearance of Granny Weatherwax as the. . .other one.

The Granny from this book is unlike the Granny from Equal Rites. I think Terry took the Equal Rites Granny and basically split her into Nanny Ogg and this Granny Weatherwax. The two witches are one of the best double-acts in fiction. You know, reading them, that Terry could spend forever writing them talking about nothing and nobody, least of all him, least of all us, would mind.

“Nothing wrong with being self-assertive,” said Nanny. “Self-asserting’s what witching’s all about.”

“I never said there was anything wrong with it,’ said Granny. ‘I told her there was nothing wrong with it. ‘You can be as self-assertive as you like,’ I said, ‘just so long as you do what you’re told.’”

Wyrd Sisters is another example of Pratchett plundering our real world as grist for his mill. The book is amazing if you read it without knowing anything about Macbeth, and then it’s amazing again if you read it after watching Macbeth. Oh, and Hamlet.

Some of the characters are itinerant actors and playwrights, having walked out of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead you feel. I don’t know where Terry’s understanding of the workings of theater, meaning actual plays and actors, comes from but the dude understood actors and plays and films and we visit them in various forms, including the Opera, many times over the course of 40 books.

There are several “Witches” books with Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg as main characters, but I think Wyrd Sisters, Witches Abroad, and Maskerade are an almost-perfect trilogy. You could do a lot worse than starting with those three books.

He had a unique stride: it looked as though his body was being dragged forward and his legs had to flail around underneath it, landing wherever they could find room. It wasn’t so much a walk as a collapse, indefinitely postponed.

Guards! Guards!

Down there – he said – are people who will follow any dragon, worship any god, ignore any inequity. All out of a kind of humdrum, everyday badness. Not the really high, creative loathsomeness of the great sinners, but a sort of mass-produced darkness of the soul. Sin, you might say, without a trace of originality. They accept evil not because they say yes, but because they don’t say no.

For me, the canonical starting point for Discworld reading. This is the first of the “Night Watch” series in which Terry really digs in to our world and begins using the Disc to tell stories about us.

Guards! Guards! like all the Watch books, is about justice. About where justice comes from, about who gives orders, and who obeys, and why. And when to stop giving orders, and when to stop obeying.

If there was anything that depressed him more than his own cynicism, it was that quite often it still wasn’t as cynical as real life.

Captain Sam Vimes—maybe the closest thing to an ‘Idealized Terry Pratchett’ Terry Pratchett could write—wants to be Dirty Harry. He’s certainly dirty (we meet him lying in a gutter, quoting Oscar Wilde, and Pratchett knew that Dirty Harry was originally going to be played by Walter Matthau because he was supposed to be literally dirty) but Harry is a cold-blooded killer and Vimes is not.

Captain Sam Vimes—maybe the closest thing to an ‘Idealized Terry Pratchett’ Terry Pratchett could write—wants to be Dirty Harry. He’s certainly dirty (we meet him lying in a gutter, quoting Oscar Wilde, and Pratchett knew that Dirty Harry was originally going to be played by Walter Matthau because he was supposed to be literally dirty) but Harry is a cold-blooded killer and Vimes is not.

In fact, Vimes expects the men under his command to run away at any sight of trouble. Some people object to being arrested! Quite violently! But Vimes is not a coward. He’s someone who gave up bravery in the face of a cruel world, but then he meets Carrot Ironfoundersson and each changes the other into something better.

Carrot Ironfoundersson is a 6’6” tall red-headed human who was raised by dwarves and so considers himself a dwarf, and why not? What is race but a social construct, after all? Speaking of dwarves and politics. . .

All dwarfs have beards and wear up to twelve layers of clothing. Gender is more or less optional.

Again, 30 years before normal people were talking about transgendered politics, Terry was screaming WHAT BUSINESS IS IT OF YOURS?! From the highest rooftops. Don’t get me wrong, dwarves on the Disc are not transgendered characters. Terry wasn’t writing about transgendered people, he was writing about everyone else and their ridiculous attitudes.

Carrot is someone Pratchett had to create because he wanted to talk about where the right to rule comes from. Carrot is born to be king and, we discover later, he knows it. He could be king. The people would rally around him. But not, he knows, because he’d make a good king, only because people tend to like rallying around strong leaders no matter their morality.

He learns this from Vimes. Had Carrot not met Sam Vimes, things in Ankh-Morpork would have gone very differently. But like Ma and Pa Kent raising Superman to want to serve the human race rather than rule it, Vimes teaches Carrot human nature. People are good at being small-minded, cruel, and capricious, that doesn’t make them bad, it just makes them people.

That understanding without judgement is one of the things that makes Pratchett a genius and someone I think everyone should read.

There are several Night Watch books, but like the Witches books I think there’s a nearly-perfect trilogy in there. Guards! Guards!, Men At Arms, and Feet of Clay are a brilliant trifecta.

“You are in favour of the common people?” he asked mildly.

“The common people?” said Vimes. “They’re nothing special. They’re no different from the rich and powerful except they’ve got no money or power. But the law should be there to balance things up a bit. So I suppose I’ve got to be on their side.”

Feet of Clay, specifically, is one of the best books Pratchett wrote, and one of the best I’ve read by anyone. It contains moments that are not only deeply meaningful, but genuinely emotional.

Don’t start there, but by all means feel free to end up there.

Death

“That’s not fair, you know. If we knew when we were going to die, people would lead better lives.”

IF PEOPLE KNEW WHEN THEY WERE GOING TO DIE, I THINK THEY PROBABLY WOULDN’T LIVE AT ALL.

Death—the character, I don’t have to describe him—shows up in a lot of Pratchett novels and some of them are fan-favorites and therefore to be avoided until you’ve gotten the hang of the series.

Death—the character, I don’t have to describe him—shows up in a lot of Pratchett novels and some of them are fan-favorites and therefore to be avoided until you’ve gotten the hang of the series.

Reaper Man specifically contains one of Pratchett’s most epic moments, but not epic in the sense of a battle on a grand scale, epic rather in emotion and meaning.

In Reaper Man Death becomes mortal. He is now a man, named Bill Door, and has to learn how to do the things living creatures do.

Eventually his powers are restored, all is set right on the Disc, but the newly restored Death remembers being Bill Door. And when the time comes, he begs the Gods of the Disc to spare someone. Something the old Death would never have done, never have even contemplated.

“SEE! I HAVE TIME. AT LAST, I HAVE TIME.”

Albert backed away nervously.

‘And now that you have it, what are you going to do with it?’ he said.

Death mounted his horse.

“I AM GOING TO SPEND IT.”

Death gives an impassioned speech, I’m not going to quote it here because it’s not a throwaway bit of humor or observation, it’s a deeply meaningful statement that moved me. It’s about the connection between all life. All life lives on death. Only we with understanding have the capacity to care and that puts a burden on us. It’s a huge emotional gut punch and it shows Pratchett’s developing strength as a writer that he went for it and hit a home run. He’d never have attempted anything like that in his early work.

Reaper Man is a mess in many ways. Pratchett was learning how to juggle two different plotlines, Hitchcock’s Meanwhile Back at the Ranch storytelling and while I think he understood it intellectually he hadn’t done it enough to make it pay off.

While Death is busy learning the morality of mortality, the Wizards are running around fighting what can only be described as the invasion into the Discworld of Shopping Malls from our world, except alive and malevolent and what? It feels like late 80s Grant Morrison, which is fine if you’re taking megadoses of peyote, but for me it felt like a failed attempt at something Lovecraftian. Maybe Pratchett isn’t a weird enough dude to pull that off.

Lots of people love it though, don’t let me scare you off. Reaper Man is a major work, but not a good place to start, I think.

Industrial Revolutions

After writing almost 30 books in 17 years (!) Pratchett had to bring the Disc more into the modern world. I say “had to” because I don’t think there was any way for him to avoid it. He’d developed his writer’s voice and his skill at plotting and character to the point where he knew he could take on larger subjects; greed, ambition, progress, but doing it uniquely his way required shaking up the Disc.

The first of these (from my point of view, we all enjoy creating categories and then slotting the books into them) is The Truth. It’s a standalone, but it sets the blueprint for the arguably better Moist Von Lipwig books to come.

Truth introduces William de Worde, a disaffected young man who stumbles into a career as the Disc’s first journalist with the advent of the printing press. He meets an absurdly pretty woman, Sacharissa Cripslock, and together they revolutionize the Disc.

It’s a great book, with great bad guys, it has depth and meaning and humanity and I strongly recommend it, but I think Pratchett felt limited by what he created in de Worde and so was forced to invent the much more interesting Moist von Lipwig.

Moist

The Moist books are basically a continuation of the Truth with a different cast. Adorabelle Dearheart is more interesting than Sacharissa but I miss the vampire photographer Otto von Chriek who collapses into a pile of ash every time his flash bulb goes off.

The Moist books are basically a continuation of the Truth with a different cast. Adorabelle Dearheart is more interesting than Sacharissa but I miss the vampire photographer Otto von Chriek who collapses into a pile of ash every time his flash bulb goes off.

Moist is chosen by the Patrician to reform one Discworld institution after another but specifically in the first book, Going Postal Moist takes over the post office and reforms it into a new machine to fight the industry-destroying and people-destroying “klacks” machines (Klacks = Fax? You get it.) Pratchett deploys some of his best and most insightful commentary on business, industry, greed, and the basic human need to feel useful here.

You did what you were told or you didn’t get paid, and if things went wrong it wasn’t your problem. No one cared about you, and everyone at headquarters was an idiot. It wasn’t your fault, no one listened to you. Headquarters had even started an Employee of the Month scheme to show how much they cared. That was how much they didn’t care.

Even though they feature two different casts, The Truth, Going Postal, and the second Moist book Making Money are a great trilogy that stand with the rest of my self-selected Discworld Trilogies, of which there’s one more. . .

Tiffany Aching

Tiffany Aching, for my money Pratchett’s crowning achievement, beats one of her greatest enemies, a Lovecraftian horror known only as The Hiver by understanding it. In fact, it’s the only way the Hiver can be beat!

Tiffany is (perhaps deliberately, I never bothered to look it up because I didn’t really want to know) Pratchett’s answer to Harry Potter. Instead of a young boy who goes to school to be a wizard, Tiffany is a young girl who goes to school to be a witch. Except the school is. . .life. It’s the world. You’re in it.

Miss Tick sniffed. “You could say this advice is priceless,” she said, “Are you listening?”

“Yes,” said Tiffany.

“Good. Now…if you trust in yourself…”

“Yes?”

“…and believe in your dreams…”

“Yes?”

“…and follow your star…” Miss Tick went on.

“Yes?”

“…you’ll STILL be beaten by people who spent THEIR time working hard and learning things and weren’t so lazy. Goodbye!”

Tiffany is the character created to replace the epic, iconic witch, Granny Weatherwax. She replaces Granny both literally, and metaphorically. She is more sophisticated than Granny. Tiffany goes where Granny cannot. Granny understood that ‘personal’s not the same as important’ and that drove her to act justly even in the face of deep emotional sacrifice.

Tiffany is the character created to replace the epic, iconic witch, Granny Weatherwax. She replaces Granny both literally, and metaphorically. She is more sophisticated than Granny. Tiffany goes where Granny cannot. Granny understood that ‘personal’s not the same as important’ and that drove her to act justly even in the face of deep emotional sacrifice.

But what Granny meant when she said “Personal’s not the same as important” was “that which is idiosyncratically important to ME isn’t significant.”

Tiffany agrees. But she goes further and says “That which is personal to OTHERS, is important.” Because it’s what drives them. It’s at the heart of what makes people bad. The absence of anyone around them willing to take the time to imagine them complexly.

Tiffany refuses to make the choice Granny made. The choice between being plugged into the world—having a life and a family—and being The Best. Being a shepherd of people, which is what a witch is, in the Discworld.

Rather, Tiffany chooses to do both and this shows remarkable growth in the author. With Granny Weatherwax, he planted his flag pretty firmly on the Steve Jobs hill of “If you want to be the best, prepare to be hated. Needed is not the same as loved.”

Did Pratchett think that? Dangerous to psychoanalyze an author—I realize the irony in me saying that in the middle of this post—I think it’s more accurate to say that Pratchett believed Granny believed that.

I sort of understand why normal people don’t read Discworld books. Maybe it doesn’t seem weighty enough, maybe it’s too British, maybe the original Josh Kirby covers were too busy to decipher.

But there’s no excuse for not reading Tiffany Aching. You’ve heard that cliché, “if you want compelling, relevant literary fiction, go to the Young Adult aisle?” This is that. I guess it’s Young Adult, but wow it works on me as a more or less Adult Adult.

The End

“This place we’re going to, it’s decadent.”

Granny Weathwewax wasn’t at all certain about the meaning of the word ‘decadent’. She’d dismissed the possibility that it meant ‘having ten teeth’ in the same sense that Nanny Ogg, for example, was unident.

All things end, including you and me and everyone we love or will ever know. Pratchett was no exception, but he checked out under what I consider bullshit circumstances.

He was diagnosed with a rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s that affected not his memory, but his ability to write. He did his best. He did what you or I would have done; he went out writing. But the last several books, I thought I detected his slow deterioration.

There wasn’t a point where things went from Good to Bad, they just got weirder and more disjointed. Plots jerked forward unnaturally. Sentences worked, but paragraphs felt haphazard.

I think Making Money was the proverbial Last Good Discworld Book, although this is a deeply personal judgement and every reader will draw that line in a different place or no place. It wasn’t that the next book, Unseen Academicals was bad, it just didn’t hang together as well as a story. But not every Discworld novel before this worked equally well, sometimes (in my opinion) the dude struck out. When you write a book a year for 40 years, that’s gonna happen!

If he had a weakness it was in his bad guys. I think in balance, looking back at the series, each book is only as good as its antagonist. Hat Full of Sky’s Hiver is a weird idea and so the book lacks something Wintersmith has, thanks to its titular bad-guy.

Finally I Shall Wear Midnight felt like a copout. I felt like he was giving his heroine a happy ending in spite of everything she’d done to earn the right ending which would have involved the death of Granny Weatherwax.

Replacements

I’d long felt that Terry knew some kind of ending had to come, and so wrote a second generation of characters to take over for his first generation. Eventually Moist would replace the Patrician, something it seemed like both of them understood without ever talking about. Eventually Vimes would finally, really, retire or, more likely, die in the line of duty.

Eventually Granny Weatherwax would die, and Tiffany Aching would become the Discworld’s Witch Supreme.

So when that didn’t happen in I Shall Wear Midnight and Tiffany instead got a happy ending, I felt like Pratchett had chickened out, developed too much affection for his characters.

Buuut I may have been hasty in my judgement. I’ll say no more, read the books for yourself.

Zappa and Schama

Finally, there is a sense that the people who make the art we love should be good people. It’s a very American notion, I think. As a culture we’re profoundly uncomfortable with the notion of Art. Simon Schama once said “Americans think great art should lead to democracy.”

He didn’t mean that literally, he meant “Americans see ‘democracy’ as the highest attainable cultural ideal and therefore all art should in some way further it.” There’s a lot of truth there, we don’t like art that challenges us. We expect our art to be moral and appreciating it should therefore make us more moral.

Meanwhile Frank Zappa explained that Americans are uncomfortable with anything that doesn’t have a practical purpose and so get confused by Art, unless it makes a lot of money. Hard to argue.

Great paintings don’t make the news, unless they go for millions at auction. It’s the only time anyone ever talks about paintings in America. We don’t care about film, as a culture, but we follow the box office like movies are sports teams. You can get a lot of eyeballs on your website covering how much which movie cost to make, how much it earned, and who got cast in which roll. You’ll get eyeballs grossly out of proportion with how many people actually go see the movie.

So the notion of a complete shitheel making great art is something we can’t wrap our heads around, because we never really got onboard with the idea of art for art’s sake. In spite of almost 100 years of lions shouting it at us.

But amazingly and contrary to so many other experiences, the dude who wrote the Discworld appears by unanimous consensus to have actually been the moral, down to earth, funny, relatable person you might wish he was if you were wishing.

That doesn’t mean he was a uniformly jolly fellow. A moment’s thought reveals to the habitual Discworld reader that Pratchett hated injustice, as his friend Neil Gaiman explained. He could get angry, but about the right things. The things we should all be angry about.

Part of his amazing persona was his connection to his fans. He loved them. He never forgot the experience of being a wage slave at a job he didn’t exactly hate, but certainly didn’t love.

I, Fan

I experienced a micropratchett of that attitude when, on Usenet—now long forgotten—I wrote to Pratchett and told him that not only does his work make me want to be a better writer, it makes me want to be a better person.

He wrote back. Back then, he wrote everyone back. He couldn’t not write you back. . .that would be rude! His level of engagement with his fans dwarfed any other writer!

“What can a humble man say, except ‘thank you?’” Wow. I mean, I assume he told lots of people that, it’s a good way to receive a compliment from a stranger, but he showed a considerable amount of grace in his correspondence with us, his readers.

I mean, you can accuse him of being provincial or sentimental, but these seem hollow observations. Yes he was proudly working-class, yes he regularly deployed sentiment in his work, but he earned it. He did the work for it, it’s not cheap or easy in his books. Understanding comes with a price.

I’m a professional writer now, I write for video games and I write for myself and when things are working well, my readers say things to me like (actual quote) “Your main character makes me want to be a better person.”

Man, that’s Terry Pratchett! That’s where I got that all from! He did something so many authors seem incapable or unwilling to do, he dared to think he could interpret the human experience for us and when it worked. . .it changed us.

It made us better people.

That’s some good writing! What are you waiting for?!

My first novel

My first novel My new novel.

My new novel.